My Therapist Said to Look for Only One Quality in a Partner

There’s a popular TikTok video right now (we’re talking 15 million views) in which a young blonde woman called “girl on couch” asks songwriters to make a dance song from the following incantation:

“I’m looking for a man in finance,

Trust fund,

6’5”,

Blue eyes”

The results have been nothing sort of hilarious and always very entertaining. This sort of collaboration is truly the best of the internet. It speaks to the fun it’s possible to have when we play “yes, and,” seeing someone’s bid and raising it one.

Her video has spawned infinite spinoffs, like this one:

“I’m looking for a man in freelance,

5’6”,

Tattoos,

Bushwick”

And on and on for every type.

Last year when I started working with a new, exceptionally wise therapist (as was detailed in this blog post about finding sanity for the first time in my life), I told her that I was ready to meet someone who could be a life partner and that I could use some help in figuring out what I may be doing to self-sabotage.

After we had been working together for several months and she was pretty well-acquainted with my particular flavor of The Trauma™, she asked me, “Well, what are you looking for? What qualities?”

I’m fairly certain I let out a big sigh followed by a grimace, my mouth pulling apart at the ends in a downward frown, not unlike the one made famous by actress Florence Pugh.

“I don’t really know if I trust myself to know what I’m looking for,” I shared. “Whatever it’s been, it’s not working.”

Which isn’t entirely fair to me or to the men I’ve loved. I don’t deem any of my past relationships “failures” just because they didn’t last forever. I have dated and been in relationships with wonderful men who helped me grow in innumerable ways. We put forever romantic relationships on a pedestal, invalidating all the other durations. We also put romantic relationships ahead of all other relationships like friendships or family ties—although the power of strong friendships seems to be a popular idea lately.

People my age participate in long-term committed partnerships or marriage less than our forbearers did.

Share of Americans who were married between the ages of 23 and 38 in 2020, by generation (source)

This is a big change! Despite its waning popularity, which is due to a combination of religious association/participation declining, equal economic opportunities for women (such as being able to have a job, make nearly the same pay, open a bank account and a credit card, etc), and present economic barriers for younger generations to attain major milestones (the great recession of 2008, massive student loan debt, high cost of living, etc), attaining a forever relationship still takes up a lot of space in popular culture and things people say they aspire to achieve—that’s my experience in conversing with my peers, elder millennials, anyway.

There are health benefits of marriage; certainly for men but possibly also for women. There are economic benefits. There are life satisfaction benefits. That being said, I like living in a world in which every person can choose to participate in committed romantic partnerships/marriages OR not.

Back to the conversation with my therapist about what qualities to look for in a partner.

She waited patiently as I grimaced so I shared a few things: “Umm, I guess that they’re the type of person who is committed to personal growth, and umm…they like to read and discuss ideas. And we share values.”

Now, if there’s one thing about my therapist Melanie, it’s that she is no-nonsense. She doesn’t beat around the bush.

“Those are okay,” she cut in. “But there’s really just one thing you should look for in a partner.”

“Oh THANK GOD someone finally has the answer so I don’t have to wing this!” my brain exhaled at me on the inside, relieved.

I cocked my head, ready to hear it.

“They need to care about you.”

Read that again.

They need to care about you.

All the other stuff is extra (especially the superficial height and eye color). Without this, there can be no healthy relationship.

I’ve had about a year to ponder this and decide its level of truthiness. I look back and I’ve never been in a committed relationship with someone who didn’t care about me.

But.

Are they able to care about me in the way that I need to be cared for and about?

I’ve decided her 1 criteria is the most important one but I would adjust it and say, “Can they care about you”? Are they able to? Are they making an effort to get to know you and your needs?

And behind that, “do they know themselves and their needs?” It’s going to be impossible to address someone else’s needs if we don’t know our own.

And what does “care” mean anyway?

There are many reasons we may not know how to care for and about one another.

Many years ago I bought the 1990 book An Adult Child's Guide to What's 'Normal' because I wasn’t sure which needs it was reasonable to have. Luckily this manual exists and it’s thorough! Chapter 1 is a banger: 65 Characteristics of Adult Children Becoming Functional People.

Item #1:

“We are people who hit age 28 or 39 or 47 and suddenly find something is wrong that we can no longer fix by ourselves. Then we make a choice to get in recovery, seek help, do a lot of painful work and then live happy lives.”

They go on to explain on pg10:

“Much of this book grew out of a series of workshops that we do entitled ‘Co-Dependency Traps: Getting Hooked And Unhooked’ The Traps we get into are the result of our dysfunctional pasts. In fact, the Traps we get into are re-enactments of patterns from our childhoods. This means that as we were growing up in our families, each of us was exposed to certain rules about living, getting our needs met and interacting with each other. We learned about men from the men in our families. We learned about women from the women in our families. And we learned about ourselves from the way we were treated in our families.

If we were ignored, we will grow up to ignore, ourselves and our needs as adults. If we were hurt, we will hurt ourselves as adults. If we were physically or emotionally seduced as children, we grow up and become either seducers or victims or both.”

My childhood was a good mix of dysfunction and function. I learned how to work hard, how to fail and start again, how to ask for help, and how to be a bold and courageous woman, always seeking the truth and challenging the status quo. My parents are brave, compassionate, and kind.

But there are also legacies of abandonment, substance misuse, war, poverty, and other features of the human condition. Particularly in the United States, we’re all refugees from another place—communities our ancestors had to leave behind to start anew, traumatizing from the very start.

Our ancestors came here probably not fully understanding that they were signing up for a bizarre experiment in capitalism and hyper-individualism. We get brought up in the US thinking we don’t need each other—that we aren’t interdependent. We get caught up in consumerism and materialism and then wonder why we’re so miserable. We drive alone in our cars each day to work, sit alone in a cubicle, drive back to our houses, separated by a fence and a lawn, watch some TV, then rinse and repeat. Corporate control of our lives is total. Did you know that even things we take for granted like baby diapers and baby formula have lobbyists, restricting paid parental leave and marketing fear so that Americans will buy more of their products? Read about The political economy of infant and young child feeding: confronting corporate power, overcoming structural barriers, and accelerating progress in The Lancet, 2023.

Dr. Darcia Narvaez says in her book Restoring the Kinship Worldview (I’m interviewing her about this book next week and you can join! RSVP here):

“We have forgotten what children need to thrive, what normal child and adult behavior are, what a healthy society looks like. We are now into generations of disorder, disorder that starts from the ground up neurobiological, leading to dysregulated, suboptimal human functioning. For example, coercion like spanking is one of the worst things to do to a young child—it disorders the mind wounding the spirit/soul/psyche, and makes the child susceptible to wétiko and other psychic viruses. Then the impaired adults, from the top down, make poor judgments about how to run society to keep the same cycle of undercare and disorder going (or going worse), because they have not experienced better, and because the cultural stories that those with power tell are that this is the best it can be and that we must “eliminate” the problematic elements (humans or viruses).”

She talks about how human beings have evolved to nurture our young—she calls it “the evolved nest” (which I interviewed her about in this podcast episode)—but that we have stopped nurturing as a whole, instead raising children in home environments of mostly fear.

“I think deception in civilized countries starts with poor baby care, where the baby is told ‘I love you’ by a parent and then left alone, left to cry, or forced into an adult schedule. That doesn’t feel like love. It’s a lie.”

“The amount of lying that has gone on in the USA recently is astounding. In his book Fantasyland, Kurt Andersen argued that Europeans were lured to the Americas with false advertising, and he think that has made Americans susceptible to fantasy ever since. In the USA, people are constantly manipulated, smothered in propaganda from corporations primarily, and now significantly so by politicians funded by oligarchs.”

bell hooks talks about this deception as well in her book All About Love:

"There is nothing that creates more confusion about love in the minds and hearts of children than unkind and/or cruel punishment meted out by the grown-ups they have been taught they should love and respect."

I reflect on her book All About Love in this piece.

I don’t know that I’ve particularly chosen uncaring partners in the past as much as I’ve had to swim upstream, fighting the current Western colonial and individualist paradigm, to understand what care and mutual interdependence mean—what they feel like in practice. I’ve had to figure out what it feels like to care about myself and to extend that same care to everyone around me—lovers, friends, family members, strangers—everyone. And to grieve how our lack of caring is now destroying our home: Planet Earth.

In Restoring the Kinship Worldview, there’s a chapter on mutual dependence (ch13) that starts with an essay by Jack Forbes (Powhatan-Lenape, Delaware-Lenape; 1934-2011) and says:

“I can lose my hands, and still live. I can lose my legs and still live, I can lose my eyes and still live. I can lose my hair, eyebrows, nose, arms and many other things and still live. But if I lose the air I die. If I lose the sun I die. If I lose the earth I die. If I lose the water I die. If I lose the plants and animals I die. All of these things are more a part of me, more essential to my every breath, than is my so-called body. What is my real body?”

My struggle to find a relationship full of care is perhaps the universal struggle to find care in our present-day “dominator society,” a term coined by author Riane Eisler and repeated often by Dr. Narvaez in her works.

In The Chalice and the Blade: Our History, Our Future, Eisler writes:

“Both the mythical and archaeological evidence indicate that perhaps the most notable quality of the pre-dominator mind was its recognition of our oneness with all of nature, which lies at the heart of both Neolithic and the Cretan worship of the Goddess. Increasingly, the work of modern ecologists indicates that this earlier quality of mind, in our time often associated with some types of Eastern spirituality, was far advanced beyond today's environmentally destructive ideology.”

Before the New Testament ushered in the era of male God worship and the patriarchy, there was a sense of interconnectedness and partnership with the earth and other living beings.

In an era where we struggle with mass species extinction, a climate crisis caused by our obsession with fossil fuels, deforestation, pollution, and other existential threats, all in the name of capitalism and rewarding shareholders, how can find our way to deep caring? It’s a Herculean task for any one of us to wake up and choose dissention.

Finding male partners who care

I’ve never had the stereotypical American male partner who weaponized their incompetence, feigning ignorance on how to do the dishes or laundry. I’ve always dated mature, tidy, and respectful men. And they’ve demonstrated they care about me in ways big and small.

My first significant long-term partner, with whom I was in a relationship for four years in my early 20s, used to pack me a lunch every morning. There was a point in our relationship in which he was working a job that ended at midnight. He would get up early while I was showering, pack my lunch, then go back to bed. This felt incredibly nurturing.

A more recent significant other would make me coffee and toast while I took early morning Zoom calls, quietly bringing it in just off camera and setting them gently and lovingly on my desk.

I dated a man briefly several years ago who would buy and bring me back a gift every time he traveled. He would give me the biggest, warmest hug upon first seeing me each and every time we saw each other, immediately wanting to know everything about how I’d been since we were last together.

One long-term partner would constantly remind me of my full potential. “I’m seeing more for you in X area,” he would encourage me. “This is your true calling.” Indeed I challenged myself to do bigger and better things while we were together including paying off a large amount of credit card debt, applying for, attending, and graduating from graduate school, and running longer and faster races.

I date warm, caring, kind, patient, loving, thoughtful, encouraging, creative men. This is most likely a hold-over from all the functional qualities of my childhood. I feel nothing but gratitude for so many of the men who have loved me.

And yet…

There have been moments of violence as well. There have been men who wouldn’t take no for an answer. There have been men who yelled. Men who quietly raged. Men who forgot my humanity. Men who objectified and cat-called. Men who called me a “girl” at the office. Men who paid me less than my male colleagues. Men who were threatened by my competence. Men who rolled their eyes at me.

Waking up to the horrors and reality of the patriarchy has been the hardest work I’ve ever done. It was 2016, after being assaulted by my Airbnb host in Iceland when I started to question everything I’d experienced in my life—when the naivete of youth was ripped from me, at age 31. I started a feminist book club with a group of women and began the arduous process of unlearning. I was horrified to realize I’d normalized so much violence at the hands of men—gone numb to it. We must have all been waking up that year because 2017 brought the much-needed #metoo movement in which we finally said, “This is not normal and we’ve had enough.”

Writer Nora Samaran wrote a brilliant essay at that time, “The Opposite of Rape Culture is Nurturance Culture”. Here is an excerpt:

“Violence is nurturance turned backwards.

These things are connected, they must be connected. Violence and nurturance are two sides of the same coin. I struggle to understand this even as I write it.

Compassion for self and compassion for others grow together and are connected; this means that men finding and recuperating the lost parts of themselves will heal everyone. If a lot of men grow up learning not to love their true selves, learning that their own healthy attachment needs (emotional safety, nurturance, connection, love, trust) are weak and wrong – that anyone’s attachment, or emotional safety, needs are weak and wrong – this can lead to two things.

1. They may be less able to experience women as whole people with intelligible needs and feelings (for autonomy, for emotional safety, for attunement, for trust).

2. They may be less able to make sense of their own needs for connection, transmuting them instead into distorted but more socially mirrored forms.

To heal rape culture, then, men build masculine nurturance skills: nurturance and recuperation of their true selves, and nurturance of the people of all genders around them.”

In John Gottman’s 2016 book The Man's Guide to Women: Scientifically Proven Secrets from the Love Lab About What Women Really Want, he tells a story in the beginning about a workshop he taught in which both men and women were in the audience. “Raise your hand if you felt fear for your safety in the last month,” he said to the attendees. All the women in the room raised their hand and maybe only a couple of the men. “Keep it up if you felt unsafe in the last week.” Only women’s hands remained, and many of them at that. “In the last day?” Many women’s hands stayed up. He shared the astonishment from the men in the room.

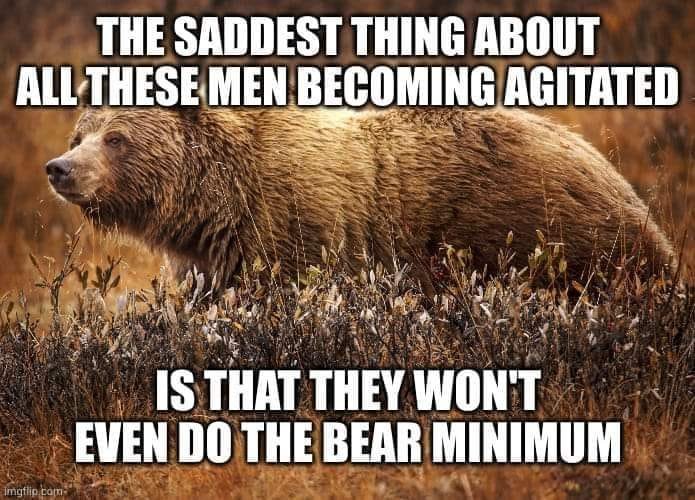

He wishes men would understand this one thing: women do not feel safe. We especially do not feel safe with men, as the recent question being posed on the internet, “would you rather encounter a man or a bear in the woods?” is showing us in which women are choosing the bear.

What is the bare/bear minimum we need from men?

I think it needs to go further than thoughtful gestures of interpersonal care, as nice as those are. We need men to care about ending the legacy of violence against women at every level: economic, psychological, sexual, and physical. The macro and micro-aggressions. The interpersonal and the systemic.

The World Health Organization shared a snapshot of violence against women worldwide:

Population-level surveys based on reports from survivors provide the most accurate estimates of the prevalence of intimate partner violence and sexual violence. A 2018 analysis of prevalence data from 2000–2018 across 161 countries and areas, conducted by WHO on behalf of the UN Interagency working group on violence against women, found that worldwide, nearly 1 in 3, or 30%, of women have been subjected to physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner or non-partner sexual violence or both (2).

Over a quarter of women aged 15–49 years who have been in a relationship have been subjected to physical and/or sexual violence by their intimate partner at least once in their lifetime (since age 15). The prevalence estimates of lifetime intimate partner violence range from 20% in the Western Pacific, 22% in high-income countries and Europe and 25% in the WHO Regions of the Americas to 33% in the WHO African region, 31% in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region, and 33% in the WHO South-East Asia region.

Globally as many as 38% of all murders of women are committed by intimate partners. In addition to intimate partner violence, globally 6% of women report having been sexually assaulted by someone other than a partner, although data for non-partner sexual violence are more limited. Intimate partner and sexual violence are mostly perpetrated by men against women.

Knowing this information, speaking up, and taking action is care. To continue to be aloof as to the realities of what women experience is to choose violence against women.

Learning how to care for myself

Certainly on an individual level I have struggled to figure out how to best care for myself. I shared in a reflection of Ocean Vuong’s book On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous that I wrote last fall:

I first started to consider the ways that the violence of war is inextricably linked to the violence at home behind closed doors upon reading trauma researcher Judith Herman’s book Trauma and Recovery. "The conflict between the will to deny horrible events and the will to proclaim them aloud is the central dialectic of psychological trauma. People who have survived atrocities often tell their stories in a highly emotional, contradictory, and fragmented manner that undermines their credibility and thereby serves the twin imperatives of truth-telling and secrecy. When the truth is finally recognized, survivors can begin their recovery. But far too often secrecy prevails, and the story of the traumatic event surfaces not as a verbal narrative but as a symptom."

War had seemed so far away for me, a child of the prosperous 1980s United States of America. It was intangible. But addiction was near and dear. I couldn’t connect the ways my ancestors fled their war-torn homelands seeking a better life, bringing their traumas with them, getting blood on their hands in the process, pillaging land and lives as they pursued their own peace, with the way I wanted to, as Vuong puts it, consume “everything you could crush into a white powder.” I couldn’t see how those things fit together and so I carried the weight of personal shame around with me along with the accompanying inner voice taunting me to just drown already.

Vuong doesn’t tell the story of how the pieces fit together. He shares the intensity of feelings and relationships and moments. In them we sense the story—we can see, hear, smell, taste, and touch it. It coalesces into a whole narrative, the reader filling in the blanks.

The blanks I can best fill in are the depths of despair and depravity at the bottom of the ocean of addiction. Way, way down there at the bottom, in the pitch black, is the simple yearning for “ma,” who the novel’s protagonist writes to. We yearn for the wholeness of complete love—whole attention, whole wanting, whole belonging. The white powders get us there when we can’t seem to find the way or when the way was never paved for us. Addiction is “one of the most human things. It is the body and the mind deciding to find a way out. We have this desire to be OK, to feel better and that amplifies the horror all around us.”

Not caring was an adaptation to some of the elements of my childhood. I entered adulthood feeling generally pretty numb and primed for addiction to substances. This video is a great overview of neglect-to-addiction-pipeline:

“Oh I don’t mind.”

“No, I don’t care.”

“I’m not mad.”

“I never get angry.”

These are some of the things I can remember my 18 and 19-year-old self-thinking or saying out loud. The substances swooped in to provide a sense of feeling, warmth, and nurturance.

This is a great visual of what’s behind addictions of all types:

Rehab at age 20 followed by years of healing that included therapy, yoga, meditation, coaching, workshops, books, and every teaching I could get my hands on has resulted in the development of a sense of self-worth that’s not dependent on achievement, the ability to set boundaries, the ability to feel feelings deeply, and the ability to label and defend my needs.

Alice Miller wrote in The Drama of the Gifted Child: The Search for the True Self:

“The true opposite of depression is neither gaiety nor absence of pain, but vitality—the freedom to experience spontaneous feelings. It is part of the kaleidoscope of life that these feelings are not only happy, beautiful, or good but can reflect the entire range of human experience, including envy, jealousy, rage, disgust, greed, despair, and grief. But this freedom cannot be achieved if its childhood roots are cut off. Our access to the true self is possible only when we no longer have to be afraid of the intense emotional world of early childhood. Once we have experienced and become familiar with this world, it is no longer strange and threatening.”

An Adult Child's Guide to What's 'Normal' has chapters on learning how to feel fully:

Feeling feelings was work I started in earnest in 2016 after the Iceland assault incident caused a full emotional breakdown. There can be no care when we stay numb to our feelings and wounds.

Many of us avoid doing the work to acknowledge where we feel hurt because we’re afraid that we’re opening the flood gates and we’ll never be okay if we let the hurt out. When I first started to let myself feel fully, I cried every day for months. But then life got so rich, meaningful, and beautiful.

Now I say words of gratitude when I experience difficult emotions. “I’m grateful for this sadness because feeling fully is what makes me alive.”

Finding a partner who cares

My therapist’s words were simple but the ideas are complicated.

“They need to care about you.”

Can they care care about me?

What does this look like in practice?

Do they care about who I am and want to see me grow and develop?

They want to see me flourish?

They are curious to know me?

They care about themselves—they take good physical and mental care so they have a full cup to pour from?

They can ask for what they need and also set and keep boundaries?

They can face conflict head-on, even if imperfectly?

They aren’t blaming others’—they take responsibility for how their thoughts, beliefs, and behaviors create their reality?

They care about violence against women globally stand up for women’s rights?

They care about the destruction of our home, the earth, and all living beings?

They challenge uncaring paradigms such as colonialism, racism, and capitalism?

They’ve examined their love inheritance and sought to heal and repair wounds?

Of course, I must also embody and practice these things.

My song of the summer would go a little bit like this:

“I’m looking for a man who cares

Any height

Soft eyes, soft heart”