Behind Every Harsh Word: The Wounds That Make People Mean

I just got out of a relationship with a person who was often mean and his small acts of meanness have been on my mind. Though small, they can add up to create an overall relationship tone of agitation, edginess, and mistrust. Many mean people say, “I’m just joking!” but mean comments aren’t usually funny—they serve to undermine the other person while giving the mean-sayer a little bit of power. They’re the little bubbles popping up from a deep, sinister caldron of unrest: insecurity. And the meaner the person, the more insecure they are.

Breakups are a particularly mucky time of reflection. We find ourselves asking questions like:

What did I miss in the beginning?

What were the signs that this wasn’t going to end well?

What does this say about me that I picked the wrong person or didn’t show up as my best?

What can I do better next time?

What can I learn?

For the complete background on this relationship and breakup, check out my dating blog page, Romance by Rail. I traveled to 9 countries in 2024, connected with about 20 men, going on dates with 12, and starting and ending 1 relationship.

Lots of Little Jabs

He spouted a lot of little jabs. I’m normally a “1 strike and you’re out” type of gal when it comes to meanness but in this case, I brought it up right away the first time I noticed it and he took accountability, apologized, and then really worked on catching the comments. I noticed a difference and I appreciated the intentional work. I stuck with him.

One of the jabs came as we were negotiating the deepening of our relationship and my moving in with him. It came in the form of this text message with an image:

It’s a picture of his freezer, with an intensely thick layer of frost over every surface—something that will take time to sort out, whether scraping it out or turning it off to let it melt and then mopping up the puddle. It’s an inconvenience, not to mention the energy wasted by having the freezer open long enough to get that thick layer.

The text was passive-aggressive: “Apparently, someone didn’t really close the door of the freezer.” Who is this mysterious someone? It’s implied but not explicitly stated that that person was me.

I remembered opening it. I was standing in his kitchen in his home outside of Paris, France, making a joke about where I’d put all my American frozen TV dinners. I was negotiating what the kitchen would be like when I moved in with more of my things in a couple of months, after spending the holidays in California. I’d been living with him at this home for a month and we were making plans for our future. I found his French refrigerator and pantry to be much smaller than those in the States. He liked to go to the market each day and buy the freshest foods—as is customary in France. I tend to like to store more food at home, buying larger amounts of food for the week ahead—as is customary in the US. “We’ll rearrange some things and make some room for what you need,” he said, referring to my need for several kitchen appliances such as a food processor, blender, and juicer, which I have at my condo in Boston.

But still I had some anxiety about the transition: “It’s just going to be so different for me to be here. And this is your home, not mine, your country, not mine.” I noticed the empty spaces where words of reassurance were supposed to be. “Does he even want me here?” I often thought. Sometimes I outright asked, “Do you even want me here?” He would say yes but then his actions would betray him. For example, he didn’t get specific about how he’d make room in his kitchen—which was already full with his things.

That’s the context for this text, which could be read as either playful or mean. In this case, I was already insecure about moving in with him and had already noted the ways he wasn’t making space for me—both physically and metaphorically. I had opened the freezer that day and made a little joke about American frozen foods but behind that was a plea for security between us.

In small refrigerators, such as the one in his French apartment, the freezer is often just a little plastic box inside of the main refrigerator door. I hadn’t realized that I need to snap the door closed, not just push it. There must not have been a magnetic hold on it—but I didn’t know.

A non-passive aggressive way to tell me I’d ruined a part of his day (that he’d have to spend fixing my mess) would have been: “Whoops! Looks like you didn’t close the freezer door all of the way. I should have told you that it’s kind of tricky. You have to push it until it clicks closed otherwise it gets ice like this. Now you know for next time.”

In this way, he’s a welcoming steward of his home, guiding me warmly through its various quirks.

The way he chose to communicate, however, was through an indirect dig. Someone (who knows who?!) did this wrong. Was he mad? Annoyed? Was he even talking about me? Did he do it? His 11-year-old son? How was I to know?

In that moment, in his passive and indirect way, he was not only telling me about his vague annoyance at someone, but he was communicating something much deeper: that he wasn’t picking up on my insecurity about moving in with him. He’d missed the emotion behind the moment when we were standing in his kitchen, negotiating how much room I’d get to take up when I moved in. He’d missed what was not said: my underlying fear about taking up space in a place that wasn’t mine and my need to feel his commitment to our relationship.

In the best circumstances, I’d ask for more clarity in response to his text, or take a guess at what he was trying to communicate. If I had been feeling secure, maybe I could have even laughed it off and apologized, saying, “okay, I owe you a couple of hours of cleaning when I get back!”

But I froze (ooh, a pun!). I felt a dagger in my stomach. I got tunnel vision. I couldn’t find any spaciousness. “Yikes,” I replied. He dropped it.

Later on the phone I was distant. “Is everything okay?” he asked. “Sure,” I said. I hadn’t processed it all yet—I was still flooded with confusion, insecurity, and an old wound of shame—outsized for this small incident. We ended the call and I felt disconnected and lonely.

I’ll share the meanest thing he ever said but you’ll have to make it to the very end of this post.

Relationship Rule: They Can’t Be Cruel

Why are mean comments typically a “1 strike and you’re out” red flag for me? It’s because it’s merely the outward and visible symptom of a much deeper problem: insecure attachment.

A blog on VeryWellMind gives a good basic overview:

“Insecure attachment is characterized by a lack of trust and a lack of a secure base. People with an insecure style may behave in anxious, ambivalent, or unpredictable ways.

When adults with secure attachments look back on their childhood, they usually feel that someone reliable was always available to them. They can reflect on events in their life (good and bad) in the proper perspective. As adults, people with a secure attachment style enjoy close intimate relationships and are not afraid to take risks in love.

People who develop insecure attachment patterns did not grow up in a consistent, supportive, validating environment. Individuals with this attachment style often struggle to have meaningful relationships with others as adults.

If a person develops an insecure style of attachment, it can take one of three forms: avoidant, ambivalent, and disorganized.

Avoidant. People who develop an avoidant attachment style often have a dismissive attitude, shun intimacy, and have difficulties reaching for others in times of need.

Anxious/Ambivalent. People with an ambivalent attachment pattern are often anxious and preoccupied. They can be viewed by others as "clingy" or "needy" because they require constant validation and reassurance.

Disorganized. People with a disorganized attachment style typically experienced childhood trauma or extreme inconsistency growing up. Disorganized attachment is not a mixture of avoidant and ambivalent attachments; rather, a person has no real coping strategies and is unable to deal with the world.”

I’ve found that while the categories are great to start identifying patterns and healing, most people fall into multiple categories depending on the context. An avoidant person may become more anxious when in a relationship with an even more avoidant type, for example. Or I’ve found, as I healed my avoidant tendencies, there was a lot of anxiety hiding underneath.

The categories come from the studies by John Bowlby, a British psychologist and researcher. According to Wikipedia,

“By the late 1950s, he had accumulated a body of observational and theoretical work to indicate the fundamental importance for human development of attachment from birth. Bowlby was interested in finding out the patterns of family interaction involved in both healthy and pathological development. He focused on how attachment difficulties were transmitted from one generation to the next. In his development of attachment theory, he proposed the idea that attachment behaviour was an evolutionary survival strategy for protecting the infant from predators.”

Along with fellow researcher Mary Ainsworth, he observed small children when they were separated from their primary caregivers and detected patterns, including the realization that children who were separated from their caregivers for significant lengths of time in infancy were more likely to grow up to commit crimes like theft.

If there is significant trauma early in life, his research showed, there would be difficulties in adulthood attaching to a romantic partner and people tended to fall into one of three categories in terms of how their behavior would present their inability to attach and trust the other—the ones listed above: avoidant, anxious, or disorganized.

One thing I love doing is asking friends who are in happy marriages how they met their spouse. I was interviewing my friend MH many years ago and she told me that she set out dating with a few different parameters, one of which was: “They can’t be cruel.” She met and married a very sweet man.

Merriam-Webster dictionary defines cruel:

cruel (adjective) - cru·el ˈkrü(-ə)l

1 : disposed to inflict pain or suffering : devoid of humane feelings

a cruel tyrant

has a cruel heart

2 a : causing or conducive to injury, grief, or pain

a cruel joke

a cruel twist of fate

b : unrelieved by leniency

cruel punishment

Other definitions of cruelty online point to an intentionality behind the meanness. Certainly, we want to avoid intentionally mean, or “cruel” people. But what about unintentionally mean people? What does being unintentionally mean mean (ooh, another pun!) about someone?

One of the fathers of psychoanalysis, Carl Jung, helped lay-people understand how someone could lead a double life, one with an outward appearance portraying stability, and a dark shadow saboteur underneath, possibly wreaking havoc in his more intimate relationships, such as those with his wife and children. These themes were formed in essays that now form The Red Book, a collection of his work from 1914-1930.

Through a century more of psychological research, we now know that it’s a person’s childhood that creates the shadow or the saboteur. The man who comes home from his dignified and celebrated public life only to abuse those closest to him has most likely experienced the time of parental separation trauma that Bowlby uncovered and defined in the 1950s.

A person who experienced a mother who was sick a lot of the time when he was a very young child, may grow up to unintentionally ignore his children. Or he might take the unacknowledged rage of that neglect out on his children through shouting, storming around the house, and blaming. Or he might make lots of mean little jabs of comments.

We might not call these reactions intentionally cruel. And yet, the abuse is there. Modern couples researcher John Gottman describes the act of “turning away” from “emotional bids,” as being a death sentence for great relationships. Couples make bids for each others’ attention and the other can either turn towards, turn away or ignore. Turning away or ignoring bids creates disharmony and eventually, according to the data from the couples he monitored, a breakup.

A little mean comment here and there, serving as a turn or push away, over time will push a person right out of relationship.

Meanness and Insecurity

Many years ago I dated a man for just a few months. We met one evening for a yoga class. In this class, I accidentally knocked over my metal water bottle not once, but twice. It clanged loudly on the hard wood floor, echoing across the large, nearly empty room.

We had both rushed into the class right at start time and hadn’t had time to properly greet each other for the date. After the class, as we stood outside the yoga studio’s building in Boston’s cold January weather, his first words to me weren’t “It’s so great to see you!” but, “Had trouble with that water bottle tonight, huh?”

I broke up with him a week later.

Here’s the connection between insecurity and meanness:

Insecure People are Stuck in Survival Mode

Insecurely attached people, those who couldn’t trust that their caregivers would be reliable and consistent purveyors of care and love, experience higher levels of fear and threat in relationships. Their nervous system is often dysregulated, making them more likely to lash out, shut down, or act selfishly as a defense mechanism. Securely attached people, on the other hand, developed years of feeling safe through repeated actions of attunement and care from their providers, enough to develop into kind, patient, and empathetic adults.

When animals feel threatened, what do we do? We lash out.

It’s important to remember that the way trauma works is that old implicit memories stored in the body (unconscious, mostly) are trying to protect us from future hurt. So we may react defensively or offensively if an old wound is triggered, in an effort to survive.

Insecure People Struggle with Emotional Regulation

The thing about the insecurely attached is that they grew up in homes without the precise emotional attunement to develop regulation skills. Parental attunement looks like noticing what your child needs at any given moment and providing it. Attuned parents offer care and soothing during difficult moments and model self-soothing strategies that their children can imitate.

In stressful homes, parental emotions may be volatile or unpredictable and there is no healthy coping or soothing modeled. Instead, they may see or experience physical violence—picture a hand punched through a wall instead of deep soothing breaths—or alcoholism or substance use. Addictions are a way to cope, albeit unhealthily, with difficult emotions.

The insecure person may use mean comments as a way to regulate themselves. In my freezer example, he may have lashed out after feeling upset that he would have to clean out the freezer. If he was secure, he could have soothed himself first, then had a direct conversation with me about his disappointment, pulling me in to connect with him. In that situation, I could take accountability and we would feel closer and better as a result.

In the yoga water bottle clang example, a secure person would have said, “It’s so good to see you again! What a fun date idea,” and waited to connect before sharing, “I got rattled by the loud noise of your water bottle falling over twice! I guess I have a strong startle response these days because I’m so stressed out at work. Do you have time to hold space for the stress I’m experiencing? It would feel good to share.”

Insecure People Assume the Worst About Others

Insecurely attached people experienced a home life in childhood in which they couldn’t rely on their caregivers. This creates a feeling of distrust about others—other people could be out to betray them at any moment. If they lash out first, they can prevent a repeat betrayal.

It’s important to note that for children, betrayal feels much more accurate than for adults. Children rely on their parents or caregivers to pay attention to them, notice them, love them, and show up with consistency and positive regard. When this doesn’t happen, it has lasting, deeply damaging impacts on a child’s nervous system and psyche. Their little developing brain wires to mistrust others and their nervous system recoils when people get to close, even people who are honest and trustworthy.

Insecurity Coincides with a Lack of Emotional Awareness

Since insecure attachment is rooted in emotional neglect or chaos, many insecurely attached people can’t label their own emotions, let alone other people’s. This leads to callousness, dismissiveness, and a lack of empathy, making them seem meaner or colder.

Just like how the freezer guy didn’t pick up on my insecurity, he probably didn’t pick up on his own feelings of discomfort either. Someone with emotional awareness and depth could have labeled a multitude of emotions:

fear of a big life change and losing his independent space

frustrated at the inconvenience

worry about the logistics of my moving in

nervous about making the right decision to move forward with the relationship

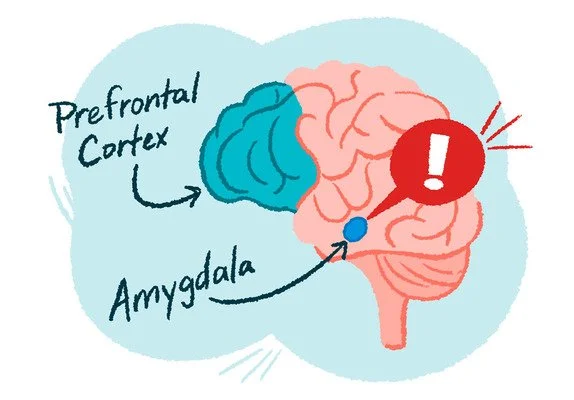

When we label emotions, we move brain activity out of the fear center (amygdala) and into the rational part (prefrontal cortex), so we can communicate well and solve challenges. Staying in the fear center is what causes us to last out through passive-aggressive comments.

image source = Ramsey Solutions

To help people develop better emotional awareness, I’ve created a free guide: My Emotional Self, A Starter Guide.

Grasping for Control is a Coping Mechanism

Those with insecure attachment have the tendency to hurt others before they can be hurt—this helps them feel incontrol and invulnerable. “If I break up with you or am mean to you and push you away, you can’t hurt me,” is the unconscious thought process. They push people away before they can be abandoned. Their abandonment in childhood was so uncontrollably traumatizing and yet they didn’t have a way to stop it. Little kids don’t have any power. To cope, they adopt mindsets that are maladaptive in adulthood: believing they don’t need love, connection, stability, trust or kindness.

Securely attached people trust relationships to flow naturally. Insecurely attached people grasp for control—by guilt-tripping, playing hot and cold, stonewalling, or being manipulative—because they don’t trust that love will stay unless they force it to.

Insecure People Constantly Position Themselves as Above or Below Others

Psychoanalyst Alice Miller wrote in her 1980 book The Drama of the Gifted Child, about the long-lasting negative impacts of cruel parenting, that depression and grandiosity are two sides of the same coin.

“Behind manifest grandiosity, there constantly lurks depression, and behind a depressive mood there often hide unconscious (or conscious but split off) fantasies of grandiosity. In fact, grandiosity is the defense against depression, and depression is the defense against the deep pain over the loss of the self.”

Insecure people are constantly comparing themselves to others and coming up either 1 up or 1 down. In order to compensate for the 1 down feeling, they make mean comments to put themselves back 1 up.

People With Childhood Trauma Can Have Poor Impulse Control

When we grow up with toxic levels of stress, we get stuck in fight or flight mode, which keeps us from fully accessing the part of the brain that helps us plan or put the breaks on certain actions. Those with insecure attachment may find themselves blurting out mean things and then going, “ugh, why did I say that?”

Should We Give Mean People a Pass?

…after all, you can’t spell compassion without “pass”.

You can see how the meanness isn’t always intentional—it’s a defense mechanism from unprocessed pain, the unconscious wounded child begging for what may have been missed.

Secure people feel safe being kind, because they were raised to trust that love and connection would be consistent. Insecurely attached people, deep down, fear love will hurt them, so they attack first or push away.

When it comes to deciding whether a mean person in your life should get more than 1 strike, I follow the change rule:

Did you clearly ask for what you need?

Do you noticed that they listened and cared?

Did they make a change?

Change is more often than not, imperfect, and people will need multiple reminders (therapist and boundaries expert Nedra Tawweb is always saying this on her Instagram). If they’re changing, attuning, learning, and growing in the relationship, they stay. If they’re shutting down, turning away, staying the same, and putting up walls, they go.

A lot of us need to work on making me sure we asked for what we need first before dropping people out of our lives.

But sometimes, when it comes to noticing consistent meanness, we need to know that we’re staring not just a cute little random bubbles, but down inside a filled black cauldron of pain—pain we can’t fix for people. Everyone must do their own trauma work.

How to Start Healing Insecurity and Meanness

🔑 The work? Healing attachment wounds so kindness and connection feel safe. ❤️ This starts with the development of The Emotional Self.

I’ve created a free starter guide, that you can download here.

The Meanest Thing!

Okay, as promised, here’s the meanest thing my recent ex-partner said to me…

I brought up that I felt like he was pushing and moving things too fast in the beginning. “I’m worried you’re projecting an idealized version of me onto me instead of getting to know me and discovering if we’re a match. I’m worried you’re just dating me because you think I’m pretty.” As a photographer, he was definitely someone who focused on physical beauty so this was a rational worry.

His response?

“You’re not that pretty.”

(Followed by “It’s just a joke!” Stay vigilant out there, ladies.)